Why do you need to learn (and follow) the genealogy research process? It's a time-tested process that leads to genealogy success. The alternative is being stuck, facing constant frustration, quitting genealogy, or worst of all—researching the wrong family tree.

In this post I'll break the process down to make it easy to understand.

- The quick and simple process "cycle" (traditional process).

- My supercharged (but still simple) Roadmap alternative.

- Hints and Tips so you're doing better genealogy, starting today.

The Traditional Genealogy Research Cycle

Traditionally the genealogy research cycle is represented by four simple steps.

- Step 1: Analyze the problem

- Step 2: Plan your research

- Step 3: Research

- Step 4: Write up your conclusion

We often further simplify this into a cycle we repeat until we actually reach a conclusion

Plan -> Research -> Analyze -> Repeat

You can probably memorize these steps of the cycle right now.

But if you start to think about how you'll follow these simple steps, they probably seem less simple.

How to Follow the Genealogy Research Process

The biggest problem with the simple "four step process" is they aren't actually steps. You will see the process (or cycle) represented in slightly different ways and all can be correct. In essence, the differences are due to the fact these aren't steps or tasks. They are more like phases.

The traditional research process took the names of actions or skills as the labels for the phases but that makes it seem like you ONLY do the named action/skill at that time---and that's an easy way to get into trouble.

Each phase needs to happen and in order but some skills, tasks, or actions occur multiple times but not necessarily in a nice expected pattern. For example, "analysis" should actually be a constant task you do. Analysis covers a lot of potential actions including writing.

Writing is the end of the process. But it's also the beginning, oh, and the middle. When you reach a conclusion you need to write it up but you need to write down all the "stuff" that happens to help you reach that conclusion, too. Plus, we rarely reach a conclusion when we follow the research process (that's why you end it with "repeat"). We need to write down all the intermediary ideas and analysis so we have it to use when we do finally get to an actual conclusion.

I know for years I thought I needed to do my analysis after I did my research and only then. That's where it was in the version of the research cycle I was taught. This actually made following the process much harder for me. I'm one of those people that naturally does analysis (even though I didn't know that's what it was called) so I was trying to force my natural tendencies into an unnatural (and actually inaccurate) process.

An Accurate Genealogy Research Process

If I wanted to accurately name the Research Process with named phases, I'd only list two phases.

- The Consideration Phase

- The Action Phase

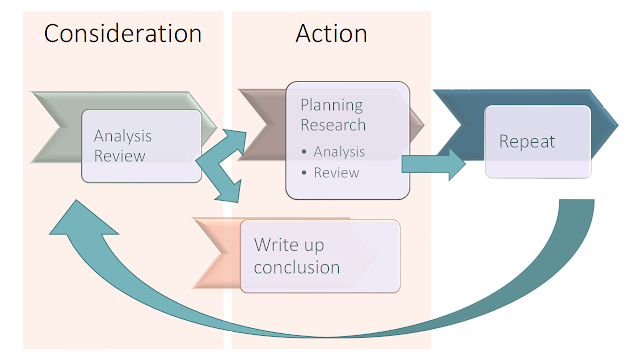

When represented as a cycle, the consideration phase would come before and after the action phase (with "repeat" coming between the two, there's a graphic below).

Two phases, even easier to memorize, right? And completely useless to follow. You can see why the process is described with the more actionable names, even if you don't know how to analyze or write-up your conclusions (and maybe you don't even know how to plan).

Here's a graphic showing the two phases plus the more traditional "steps" included.

This is meant to give you an idea that you're doing a lot of the same "steps" over and over and over again. There are plenty of other tasks you have to do but those will be unique to the problem you're working on. They fall under one of these headings.

An Actionable Genealogy Research Process

I think a better way to express the genealogy research process, in a way you can actually follow, is to make it a series of questions. To follow the process, answer these questions in order.

- What exact question am I trying to answer? (OR what is the goal I want to achieve with this research?)

- What have I already done that is related to this question/goal?

- Based on what I've already done, do I need to adjust my question/goal?

- Based on what I've already done, what sources can I use to answer my question? (this is research planning and it has more specifics than this question but this is a good starting place)

- Can I do the research I just planned? (if so, do it, otherwise plan some research you can do)

- Now that I've done the research I planned, how do my new findings relate to what I had done before? (this is analysis, write down your answer to this question to complete this pass through the process)

- If you did not find an answer or achieve your goal, repeat these series of questions.

Want to learn more?Get our email learning series with The Brick Wall Solution Roadmap.

The Writing Step (a misnomer)

You should be writing down your answers all along. Remember, "writing" is not a step in the process. Writing up your conclusion is just how you call your problem solved, so you can move on to a different problem. Remember to write during the entire process.

The Analysis Step (another misnomer)

Everything in this process is a type of analysis except actually creating the plan and the literal action of researching. Those are what I called the "Action Phase." Those are things you are doing that aren't "thinking about" or considering your problem and how you can solve it.

You should also do analysis as you research. This is essentially more "consideration." While you're researching, the analysis is what helps you keep researching. You are thinking about what else to do, look for, etc. You are considering if you've finished the research or need to use that source further.

Watch Out for This Research Pitfall!

You might also be considering if there is more research to do but be careful. You likely should "stop" researching and move back into the consideration phase then create a new plan and do the planned research. An experienced genealogist can easily follow the complete research process in this situation without it taking more than a few extra minutes. Those few minutes are worth it to write down what you're thinking. Skipping consideration and planning and continually researching usually causes issues down the road.

[There are of course exceptions to this but it's best to have warning bells going off in your head that you should NOT just keep researching but take that few moments pause to write things down. Creating a research plan doesn't need to be fancy, just written down, so a "pause" can be an accurate way to describe this. Examples of good times to just keep researching are when the repository is about to close and you'll have to leave if you take even five extra minutes or if you're literally looking at the source for the new research.]

What is In-research Analysis?

Analysis while we research is mostly things you do naturally like thinking "Oh, I see there are five people in this census household with the same last name. There are NO relationships listed but it's likely these people are related. I should capture information about these other people as well."

Yes, that very obvious "assumption" you made when you were starting out is a type of analysis. You should get better at this so you don't make assumptions (you think "they might be related" instead of thinking "that's his son") but also so you do more involved analysis just as naturally.

Analysis is not a distinct step. It's the thinking related to the mindless gathering of data. Humans do it automatically but we can learn to do it better, no matter how well we naturally do it to start with.

The questions given above are a good way to follow the research process but they are an overview that can lead to missing other key actions. I created my own version of the genealogy research process to help keep the process simple but make it more actionable. You can learn about it below.

Genealogy Research Process Alternative: The Brick Wall Solution Roadmap

If you can't tell by the title, the Roadmap is designed for a brick wall (a "brick wall" is a problem in your research that stops you due to how difficult it is. You hit a brick wall in your research and can't go further).

The only difference between the process for a new question and a brick wall is, the brick wall has research you've already done (i.e. you KNOW there is related research. For a new problem, you will have to ask yourself if you have related research/information and it might be an extremely small amount of information which simplifies the steps below).

Here's the simple version of the Roadmap.

- Focus on one brick wall problem (be specific!)

- Review your past research

- Write down what you found from your review.

- Make a plan

- Execute the plan

- Repeat

If step four is "make a research plan" then step five is "research." But I expressed this part of the action phase differently because there are two other fundamental things you need to do.

Those other two options for the action phase are education and organization.

Option 1:

When you review, you might write down that you know you did some other research but you can't find it. That means your plan in step 4 should be an organizing plan. Once you've executed the plan, you repeat (step 6) and review everything again including the material you (hopefully) found.

Option 2:

When you review, you might write down that you have questions you need to answer and those answers aren't information from your research, they are thing you need to learn. In this case, you'd make an education plan in step 4. Once you execute the plan, you repeat and review your existing information/research with your new knowledge.

You ideally create research plans that you complete in one pass through the Roadmap. You don't have to complete an organization or education plan to move on to step 6 (repeat), though. If you got organized enough to find some other research or you learned something new, repeat and review that additional material/knowledge with your existing research.

The Roadmap is meant to be a bunch of short trips through the process, not a long journey. Genealogy is an on-going journey but the Roadmap is meant to take you to a specific destination as fast as possible. By being really specific in step one and following all the steps (including writing things down so they are fast to review), you can go through the Roadmap process multiple times in a day or in several very short bits of time.

I want it to be really clear that you should repeat as often as possible. You need to be organized and you need to get education. That doesn't mean halting research for weeks or months. It could be stopping research for half an hour to Google an answer. Make sure you write down the answer you find, though. You don't want to stop research for half an hour six more times (when doing future research) before you remember the answer. If you get organized, you can find that answer as part of step 2, so you aren't stopping research at all!

Faster Genealogy with the Roadmap

With the traditional research process, ending with a conclusion makes it sound like the process should take awhile, potentially years. The genealogy research process should be performed one entire time for each research plan. A research plan can have as little as one source to check. I recommend aiming for three and no more than five. Research plans are really small!

Remember, education plans don't have to be completed before you repeat. You repeat when you learn something new that you can apply. Organizing plans can work similarly. Once you find something worth reviewing, repeat.

The Roadmap is designed to be fast to complete. If you took a stay-cation to do genealogy all day (or actually went somewhere to research for hours), you should be able to go through the Roadmap multiple times. The only exceptions are if the first time through takes a long time due to how disorganized you are or if you are using a source that you have to read line by line and that takes most of the day on its own. For the average type of genealogy research, you should go through the whole Roadmap several times in a multi-hour research session.

Following the genealogy research process makes family history research faster. But in order to do that, you have to understand some nuances of the process. The process is traditionally explained as steps but the names given to the steps are often tasks that should be done throughout the process. Learning when to do tasks and how to do them better will improve your results as well as helping you research efficiently.

Here are some hints and tips for doing better genealogy using the genealogy research process.

Hints and Tips for Doing Better Genealogy

- Write things down. This can be "reporting" but also just taking notes. See this post to learn the basics of genealogy note-taking.

- Analyze throughout the process. This isn't a "step."

- Create LOTS of research plans. Research plans should be short.

- Learn the difference between the goal of your research and a hypothesis for a research plan. You need both!

- Keep breaking your problem down and solving smaller parts. Put the parts back together when you review to get an overview of the larger problem.

- Don't forget to learn and organize, not just research.